My earliest memories are of living in a north west home with my older brother and family.

I would regularly watch him and a group of his friends playing football on concrete, with far too many players to probably be safe. He was a pretty good player, from what I can remember.

Cyrille was a popular boy, six years older than me; he would go on to be rewarded with an MBE – recognised by the world as one of the first Black football players to play for England.

That boy would become a legend of the game, with a lasting legacy that holds strong even now, nearly five years after his death.

The thing is, six years as children is quite a big gap; Cyrille and I got a lot closer as we got older. Growing up, I was probably his annoying little brother, so we didn’t hang out much at all. I would spend my time with some of his mates’ younger brothers instead.

At the school we went to, teachers and some of the older students would always say how great Cyrille was at sports, including cricket and football, but to me, back then I wasn’t really interested.

I didn’t realise just how good he was at football until at 19, he signed professionally for West Bromwich Albion.

To me, he just liked a kickabout with his mates and played for a team while training to be an apprentice electrician during the day. In his late teens, he played semi-professionally for a couple of lower league teams around his full-time job, but I didn’t think it was anything serious.

The next thing I knew, his name and face was plastered all over the newspapers, speaking of his talent as a young player – scoring two goals in his professional debut appearance for West Brom.

It was a surreal moment that, to me, came completely out of the blue. I was totally oblivious as to how much his life would change forever.

Cyrille was born in 1958 in French Guiana and moved to the UK when he was five, where I was born in 1964. We had a big extended family, who were pretty close.

I loved football, but sadly never went to watch Cyrille play during his stint as a semi-professional, before signing for West Brom. It wasn’t something we did as a family. I don’t even think my father, Robert, a fisherman born in St Lucia, ever even kicked a ball. As long as we were happy and stayed out of trouble, our parents were happy.

But seeing your brother play professionally, and being worshipped as a player was very surreal, and lit a fire in me to do the same. Cyrille was extremely proud of me when I signed to play semi-professionally for Dunstable Town, aged 18.

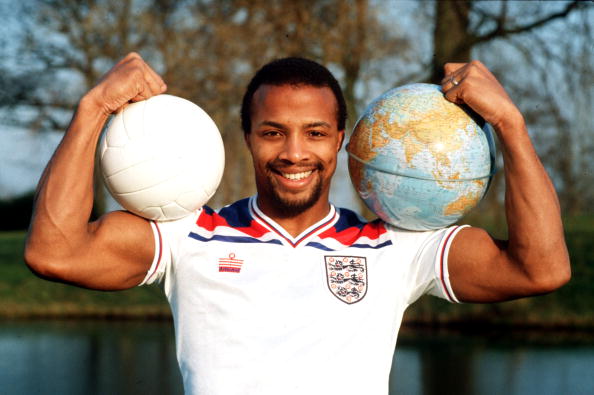

Cyrille’s career went from strength to strength, and he first played for his country, England, in 1978 as part of the under 21s team.

Unfortunately, another thing we had in common as brothers – as well as being Spurs fans – was the level of racism we both experienced as football players. At one point, Cyrille even received a bullet in the post.

I’m not sure if I would have gone on and played with my life at risk, just because someone didn’t like the colour of my skin, but he did. Admirably, he let his football and actions do the talking, rather than react.

Back in those days, if you ever reacted to racism from both fans and players, you would be the one who got in trouble. The authorities weren’t interested, either. It was difficult and relentless for us both, but it made us even more determined to score goals, and shut the bigots up.

You had to develop a tough exterior as a player. Black players like Cyrille, and his West Brom teammates Laurie Cunningham and Brendon Batson didn’t have a voice, and you just had to shrug it off.

Cyrille ended up winning five caps for England in his career, and was one of the first Black players ever to be capped by the team, alongside Cunningham and Viv Anderson.

My brother’s career ended in 1996, when he retired, aged 39, after playing professionally for Coventry City, Aston Villa, Wolverhampton Wanderers, Wycombe Wanderers and Chester City – and returning to West Brom as a coach.

He poured his heart and soul into his charity work, dedicating his life to it. He never let his success get to him, determined to be a mentor to Black youth and younger players, those who needed support, throughout his entire career – and beyond.

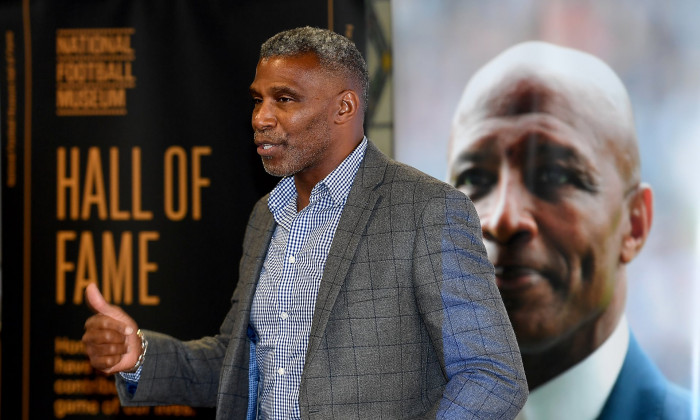

He cherished his roles as Ambassador and Trustee for charities Christians in Sport and WaterAid – and, in 2008, it earned him his much-deserved MBE.

After Cyrille passed away in January 2018, aged 59, I was devastated – as was the football world. It was surreal sharing my grief with the globe; seeing my brother’s face and familiar smile on the news outlets and Wembley Stadium, listening to the outpouring of love for him from players like Ian Wright, Dion Dublin and Brian Dean.

Wright commented on how inspirational Cyrille was as a player; how above all others made him want to become a professional football player. Believing that, because Cyrille did it, endured the racism and came out the other side an exceptional player, he could too. It was incredible to hear that he was a role model around the world.

If Cyrille was alive today, I have no doubt that he would be vocal against racism and social inequality still being so rife in his game.

The racism footballers still experience is a reflection of both society, and the sport. Racists and bigots think a football match is free game, where they can express their hateful views at no cost to them. Until FIFA and others comes down hard on racism amongst its teams, fans and players, nothing is going to change.

Now, Cyrille’s wife Julia and I are determined to carry on his legacy – setting up the Cyrille Regis Legacy Trust in his honour. The purpose of the charity is to continue the great community work he was involved in, empowering young people from across the West Midlands to live their best lives.

I’m a patron, mentor and a coach. Helping young people to achieve their dreams and overcome obstacles through the Strike a Change initiative, a collaboration with all six West Midland Football Club Foundations.

The programme targets 13-14 year olds who demonstrate a passion for football and are considered to be disengaged in school, or within their community. It feels amazing to carry on his legacy by helping others.

Racists can make you feel worthless, and that’s not what we want for Black people of any age in the UK.

Cyrille was a Black pioneer, proving that you can’t let the bigots win – fighting hatred with love for his community and being at the top of his game. And it’s a message that rings true even today.

There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think of and miss Cyrille – I can hardly believe it’s been nearly five years already. Thank you big brother, for everything!

Let Me Tell You About...

This Black History Month, Metro.co.uk wants to share the untold stories of Black trailblazers – too often missing from the history books.

Let Me Tell You About… is Platform’s exciting new series, celebrating the lives of Black pioneers from the people that knew them best: their family.

Each week in October, prepare to meet the descendants of Black history makers – and learn why each of their stories are so important to our lives today.

If you have a story to share, email [email protected].

Black History Month

October marks Black History Month, which reflects on the achievements, cultures and contributions of Black people in the UK and across the globe, as well as educating others about the diverse history of those from African and Caribbean descent.

For more information about the events and celebrations that are taking place this year, visit the official website.

October is Black History Month (Picture: Metro.co.uk)" />

October is Black History Month (Picture: Metro.co.uk)" />

Black History Month

October marks Black History Month, which reflects on the achievements, cultures and contributions of Black people in the UK and across the globe, as well as educating others about the diverse history of those from African and Caribbean descent.

For more information about the events and celebrations that are taking place this year, visit the official website.